Cauda Equina Syndrome

CAUDA EQUINA SYNDROME (CES)

Basic Anatomy:

The spine is broadly categorized into 5 segments: cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral and coccygeal. Each segment contains a series of vertebrae that can be numbered systematically for easy recognition of structures pertaining to these bony landmarks (C1-7, T1-12, L1-5, S1-5). The spinal cord is a bundle of nerve fibres which run centrally through the vertebral canal. This ordered fashion of fibres begins to taper and terminate at the conus medullaris. In adults, this is usually found at the L2 vertebral level. Inferior to this point situates a bundle of spinal nerve roots, referred to as the cauda equina or “horse’s tail†of the spinal cord. Below, the filum terminale marks the end of the spinal meninges at S2.

Causes:

The aetiology of cauda equina syndrome can be thought of as any factor which compresses the spinal nerve roots.2

Lumbar disc herniation- most commonly L4/5, L5/S1 levels. This may be secondary to degenerative disc disease, trauma, or infection

Spinal vertebral fractures or subluxation

Malignancy- primary or metastatic. Breast, prostate and lung cancer most commonly metastasize to the spine.

Spinal infection- abscess, meningitis, TB/Pott’s disease

Iatrogenic- spinal anaesthesia, post-op haematoma, manipulation

History and Examination:

Diagnosis of CES relies heavily on rapid recognition of characteristic features of the syndrome. A thorough neurological history and examination are essential in order to elicit these symptoms and signs.

History:

Depending on the patient’s presenting complaint, neurological history-taking should be tailored towards identifying and ruling out the ‘red-flags’ of CES.1,3 Broadly, a useful structure is as follows:

Introduction:

Patient name, DOB

Your name, role

Consent for history-taking

Presenting Complaint

Patients may present with back pain, as well as pain, paraesthesia and numbness in the distributions of any lumbar or sacral dermatomes. Some cases may present following trauma or episodes of mechanical stress. All such patients should be screened for red flag symptoms of possible CES.

Red flags that point towards CES include:

Bilateral sciatica

Saddle anaesthesia

Bowel/bladder dysfunction- most commonly urinary retention 4

Sexual dysfunction

History of Presenting Complaint

Onset/Duration- CES symptoms often present acutely or sub-acutely

Progression- symptoms may be worsening

SOCRATES for pain- usually low back, quick onset, sharp pain, sometimes radiating to leg or hip, associated with bladder/bowel dysfunction, very severe

Ask about features which may point to the underlying cause of CES:

Stenosis: Pain relief on bending forward/sitting

Malignancy: Fevers, night sweats, unexplained weight loss

Infection: Fevers, night sweats, vaccinations (meningitis), recent travel (TB), local sources of infection

Iatrogenic: Recent surgery, localised collection of fluid around the lumbar spine (haematoma)

Past Medical History

Recent trauma/heavy lifting

Previous hospitalisations

Previous surgeries, including spinal operations

Medications/Allergies

It is important to ask about anticoagulation in preparation for surgical management of CES

Family History

Rheumatological disease

Degenerative disc disease

Osteoporosis

Cardiovascular disease

Malignancy

Social History

Smoking, alcohol, recreational drug use

Occupation- important to understand the potential consequence on work

Ideas, Concerns, Expectations (ICE)

Patients may not be familiar with CES, therefore it is important to explain your clinical suspicion and the role of MRI for further investigation.

Examination:

Following a thorough patient history, an examination is necessary to identify the severity of sacral dysfunction if patients are complaining of red flag symptoms. Where patients are not symptomatic of clear red flag symptoms, but a history with suspicious features is present (i.e. sudden onset back pain or sciatica, rapidly worsening back pain or sciatica, or symptoms related to a possible primary cause of CES), the examination is necessary to identify or rule out evidence of CES.

The following should be carried out:

Lower Limb Neurological Examination

In the case of CES, clinical examination will elicit signs of lower motor neuron dysfunction:

Tone- hypotonia

Power- a bilateral or unilateral weakness

Reflexes- areflexia

Sensation- abnormal sensory changes

See the Geeky Medics guide here

Digital Rectal Examination

To assess for:

Saddle anaesthesia (loss of perianal sharp/crude touch discrimination)

↓ perineal sensation

↓ anal sphincter tone/loss of anal squeeze

Regardless of embarrassment, perianal pinprick discrimination should be assessed to rule out sensory dysfunction

See the Geeky Medics guide here

Abdominal Examination (brief)

To assess for palpable bladder- urinary retention

Classification of CES:

Based on clinical features, CES may be broadly categorized into incomplete vs. complete pathology. Patients with incomplete CES will complain about urinary difficulties, altered urinary sensation, loss of desire to void, hesitancy and urgency. Patients with complete CES demonstrate definitive urinary retention with associated overflow incontinence. Both classifications require urgent further investigation.

Investigations:

Most importantly, suspected CES should prompt urgent surgical referral to an appropriately equipped centre.2 Meanwhile, the following investigations should be sought:5

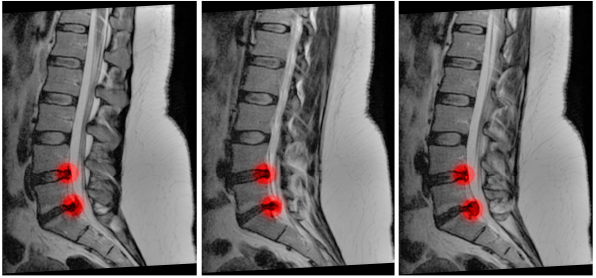

MRI Spine – ideally within 1 hour of the patient presenting, with T2 weighted sequences. The Society of British Neurological Surgeons (SBNS) and British Association of Spine Surgeons recommend that there be no hesitation in attaining an MRI for patients with suspected CES. This may be done at the nearest local centre, prior to engaging in discussions with the spinal surgery team. The MRI should be prioritized above elective cases.6 A CT myelogram may be used in situations whereby MRI is contraindicated.

Post-void residual volume (PVR) – to assess for urinary retention

Management:

Patients with suspected CES should be formally assessed using the ABCDE method. Once the patient is stable, adequate analgesia should be prescribed. If urinary retention is present, a catheter should be inserted prior to transfer to neurosurgery. Sacral observations should be undertaken frequently.

If a reversible cause of CES can be ascertained from MRI, then urgent surgical decompression should be offered. Decompression may include a laminectomy (removal of vertebral lamina), discectomy (removal of intervertebral disc) or both, as well as removal of any other compressive lesions. Specific surgical approaches will depend on the underlying pathology:

Lumbar disc herniation: Laminectomy +/- discectomy

Spinal stenosis: Laminectomy

Spinal trauma: Depends on mechanism and nature of injury

Malignancy: Surgical excision +/- decompression (laminectomy or discectomy)

Spinal Abscess/empyema: Laminectomy, evacuation of abscess +/- discectomy and antibiotics as per local protocol

*Timing of surgery for CES can be controversial. For patients presenting during the evening/night-time, some neurosurgeons argue there is no benefit in urgent surgical intervention for complete CES, and such cases may be done in the morning. This is largely due to poor prognostic factors. However, ethical considerations prohibit the investigation of such hypotheses with upper-tiered research methods.

CES is a spinal emergency and requires urgent surgical management or long term neurological sequelae that are likely to be permanent. Examples include:

Paraplegia

Lower limb numbness

Chronic urinary retention or incontinence

Chronic sexual dysfunction

Poor prognostic factors include age, gender, duration of complaints of the herniated disc, duration of CES complaints, time to decompression, saddle anesthesia, bowel/urinary dysfunction.

References:

Gardner A, Gardner E, Morley T. Cauda equina syndrome : a review of the current clinical and medico-legal position. 2011;690–7.

Lavy C, James A, Wilson-macdonald J, Fairbank J. Cauda equina syndrome. 2009;338(April).

Korse NS, Pijpers JA, Zwet E Van, Elzevier HW. Cauda Equina Syndrome : presentation, outcome, and predictors with focus on micturition, defecation , and sexual dysfunction. 2017;894–904.

Fraser S, Roberts L, Murphy E, S AF, Roberts L, Cauda ME. Cauda Equina Syndrome : A Literature Review of Its Definition and Clinical Presentation. YAPMR [Internet]. 2009;90(11):1964–8.

Rider IS ME. Cauda Equina And Conus Medullaris Syndromes. [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. 2019 [cited 2019 Jul 1].

Standards of Care for Investigation and Management of Cauda Equina Syndrome. :2018.

Mostafa El-Feky HK. Cauda equina syndrome [Internet]. Radiopedia. 2019 [cited 2019 Jul 1].

Jing Jing Chan JJO. A rare case of multiple spinal epidural abscesses and cauda equina syndrome presenting to the emergency department following acupuncture. Int J Emerg Med [Internet]. 2016;9(1).

Jmarchn. Posterolateral view of vertebrae labeled description [Internet]. Wikimedia. 2015 [cited 2019 Jul 2].

John A Beal, PhD Dep of Cellular Biology & Anatomy, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center Shreveport [CC BY 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)].